The Beast is dead.

-Ed Koch on Rudy Giuliani

I know Cloverfield was released two whole weeks before Giuliani flopped in the Florida primaries. But in the offline world, two weeks is still sometimes a short enough time span to hang a trend on. ars brevis, vita longa. We don’t have much to tie these two together, but they’re great mile markers to show our distance from 9/11.

Giuliani is a national service. He was integral to the healing process; if he didn’t come along, therapeutic America would have had to invent him. Thanks to Giuliani, it’s OK to laugh at 9/11. It’s OK for our hemp-smoking friends to scoff at the Republicans’ unstoppable fear campaign. “Looks like someone is living in the past! Contemporize, man!” We’d have a tighter parallel, more narrative resonance, if Giuliani had waited till February 5 and crashed and burned in New York, like the Cloverfield task force. But any end of an era will do.

Half the subconscious fun of the burgeoning New York disaster flick genre is anticipating the moment that will be most 9/11-esque. Is it the collapsed skyscraper or the rolling dust cloud? The mass evacuation? The rescue workers? Are those towers twins? And the guiltiest pleasure, Is it too soon?

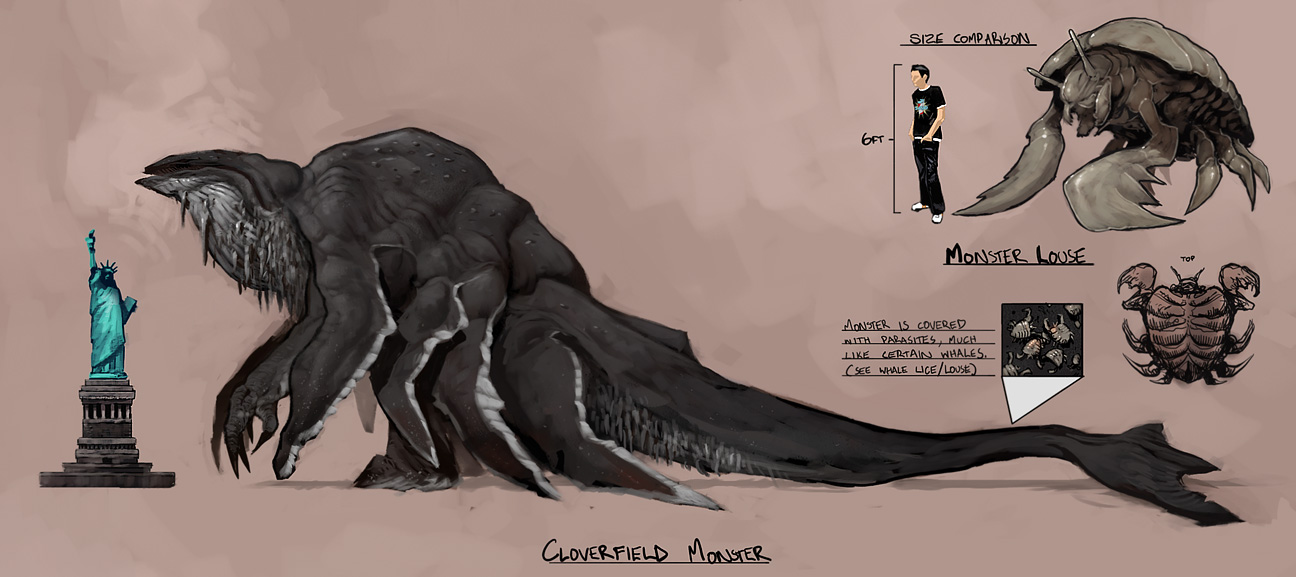

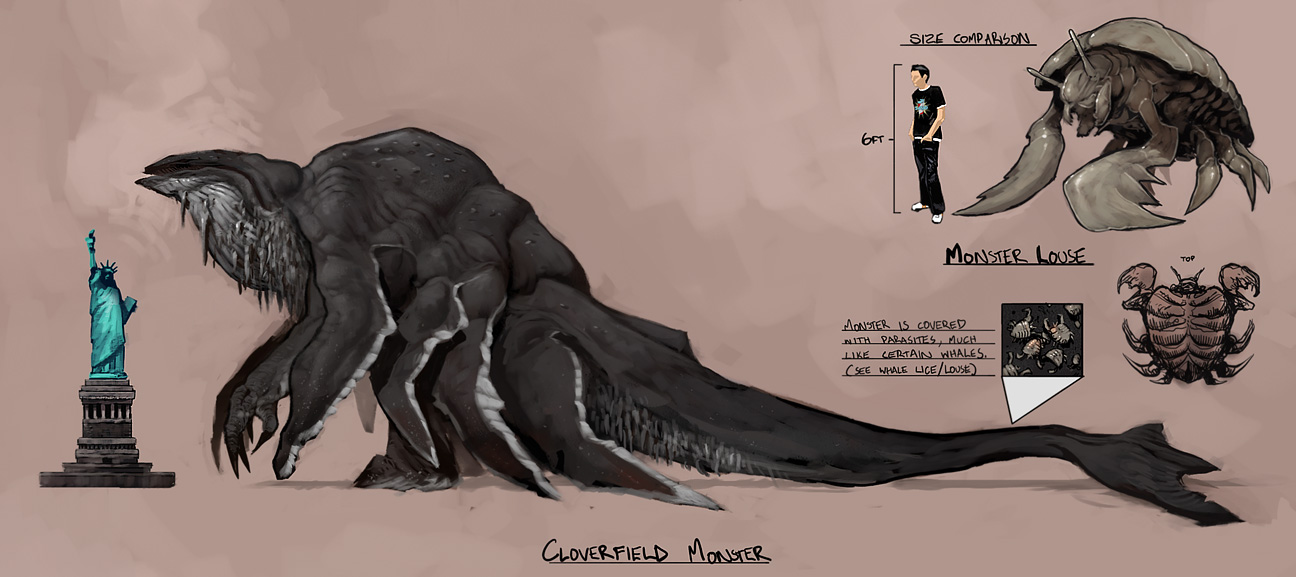

Cloverfield (known for months only by the shorthand of its release date, 1-18-08, dates being the new nomenclature of disaster) showed the seam in its fabric when plot-point character Lead Soldier tells our heroes the U.S. Gov’t is prepared to give up the island of Manhattan. The quote arrives pre-meta, like a programmatic decree from Hollywood: New York is Fair Game. ‘Ready?’ is no longer even the question for destroying New York on film. It’s open season, and the monsters have permission to do their worst.

Because New York is already gone. And no other American city ever needs to be destroyed again—we can watch movietime New York get destroyed over and over again, in eternal return. The imagery of 9/11—different, of course, from the event itself—came at us mediated, interminably looped, lodged in our brains not as memory but as movie memory. It’s familiar, it’s reassuring, it’s part of a genre. Disaster joins the list of big New York story types: Upper West Side liberals fall in love; City Kid finds American Dream through organized crime (immigrant) or dance competitions (native); Muppets (showbiz, banking) Take Manhattan.

That brings us to the Dust—the Dust on Tom Cruise’s face in War of the Worlds, the Dust on Cloverfield’s “SoHo” streets as the head of the Statue of Liberty rolls down it. That dust is less verisimilitude than homage, Spielberg or Matt Reeves quoting 9/11 like PTA quotes Scorsese. We’ve had big movies treat the Destruction in New York theme before—WotW, I Am Legend. But Cloverfield is not a big movie, on which to test the mass-market waters for 9/11 disastertainment feasibility. There was plenty of experiment with Cloverfield: would the jerky camera work? the ARG web sites? the secret title? the youtube promos? Underneath those unknown variables, the control, the safety, the sure thing—was 9/11.

None of this is the closure we had thought we’d find looking forward from the other side. We didn’t win like we swore we would, but that time is over, and so far post-post-9/11 feels better than what we had before.

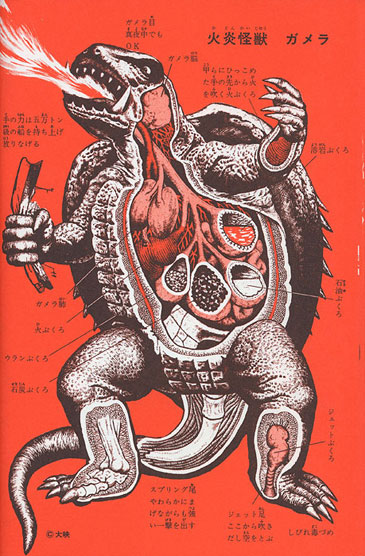

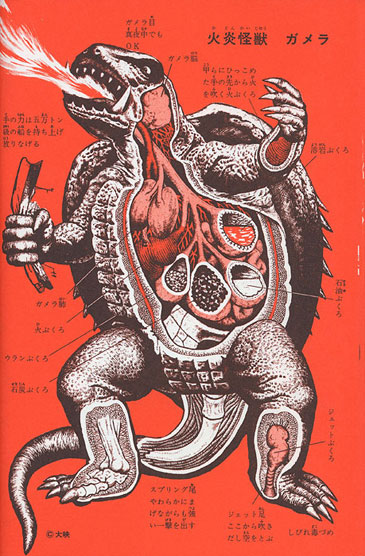

As curator of the exhibition Little Boy, Takashi Murakami proposed that Japan’s sexually stunted, violent culture of cartoons and monsters, to quote Mark Stevens’s review, “represents the strange, even psychotic response of a population traumatized by World War II, and then made impotent and infantilized by occupation.” This may be related.

Grand Theft Auto IV

Life after People

Update: Huzzah!